The Creator God who was revealed to the Jews, and the Incarnate God revealed to Christians, is not a “god,” nor even the greatest and most powerful of the gods. We refer here instead to a Reality that is, quite simply, not in the class of “gods” to begin with. A related category mistake regards the pure spirits – at least the ones we call holy.

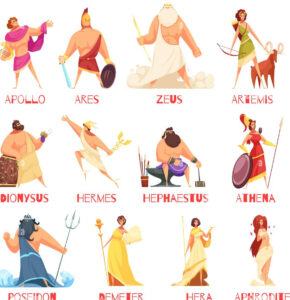

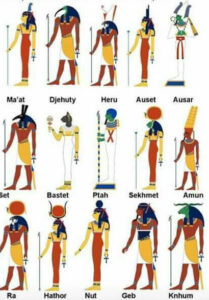

The pantheon of gods and demigods that populate the world’s mythologies, and which we also find in some forms of neoplatonic speculation (Porphyry, Iamblichus and Proclus, for instance), is a rich, intriguing but confusing potpourri of three ingredients: 1) dimmed recollections of a legitimate primordial tradition regarding spiritual hierarchies, 2) interventions – ranging from the incidental to the systematic – hailing from the wild world of “fallen” spirits, and 3) an inevitable and substantive input from the eagerly-volunteered constructions of the human imagination (including, of course, “projections” of our mind’s inner voyages, its time-honored archetypes, and – more objectively speaking – symbolic configurations of natural forces and cosmic mysteries of the “subtle” order).

The God revealed in the pages of Scripture, and also the nature and work of the angels likewise depicted (always in emphatic subordination to their Creator) are incommensurate realities when compared with the majority of the gods of the world’s non-Biblical traditions. The latter, typically – like us – are in the cosmos only by being part of it, even if possessed of greater powers than humans. The God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, on the other hand, is only in the world by means of the uniquely divine mode of transcending the world, and only beyond the world by means of the divine mode of being immanent to the world.

God is not beyond the cosmos by being spatially “outside” of it (which makes no sense at all), but rather by being, in the deepest way possible, within it. But it is a different kind of within-ness than what we are accustomed to. It is the way Dostoevsky is in The Brothers Karamazov, or Michelangelo in his David, not as a protagonist or part of the plot or a piece of the marble, but instead by being causally within the work in the most intimate way possible – an immanence without which the work could not be sustained, a transcendence without which the work could never have been produced in the first place.

With the angels things are more complex, since they do not create at all, but only bring form, organization, orientation and guidance to that which God alone creates. However, their work is so subordinate and transparent to the Creator’s sovereign acts, they virtually disappear in the performance of their tasks. They shy away from every possible veneration or free-standing cult that could feign to position their interventions as rivals to the works of the Almighty. Accordingly, their names, ranks and serial numbers should never be sought among the catalogued deities of the multiple hierarchies of the world’s traditions.

Like their God in the Old Testament, the angels, even in the New, are reluctant to reveal their names. The most celebrated and reliable surveyor of the angelic orders (who wrote under the name of Dionysius the Areopagite) carefully labels and describes the choirs and their total submission to God and the divine order, but spares us lists of angelic names. Even in his famous companion piece On the Names of God, he is more apophatic than cataphatic – that is, he urges us to focus our cognitive claims on negating all that God is not, rather than presuming to take onto our frail tongues words that say positively what God is.

We are in a very different context, and must reach for a different vocabulary, when we have before us the God revealed not in Homer or the Vedas, but in the Tanakh and the Gospel, and the angels disclosed to us not in Hesiod or the Puranas, but in the subdued acounts we find in Holy Scripture. And on a more polemical note: the “God” against whom our more militant atheists fulminate is usually none other than the fictional “Big Guy” among the gods, a kind of purely immanent superpower among competing forces of the universe. No theologically educated Christian believes in gods of this ilk.