Many attempts have been offered to defend the theory that only physical reality is real (so-called ‘naturalism’ or ‘materialism’). Although embarrassingly feeble in argument and often unabashedly ideological in inspiration, the main claim has been that there seems to be no evidence within the world around us that anything beyond mass and energy need exist in order for it all to make sense.

They do have a point, to the extent that one can conduct revealing scientific experiments and produce technological marvels without attending, explicitly, to any extra-cosmic causality. What, however, is implicit in all this tells a different story altogether, but is something I will deal with elsewhere. But even the explicit point – the apparent “functionality” of naturalism – must steer clear of a Scylla and Charybdis that could shipwreck its cogency. There exist two extremities of human experience which periodically invade our world, and when they do, promptly engulf the logic of naturalism in a swoon of either jubilation or desperation.

Most of our lives are navigated on a sea of everyday, moderate or somewhat more intense experiences of either satisfaction and pleasure, or of discomfort and pain – or perhaps an interval of limbo between the two. We try to ply these waters as best we can. If that were the whole story, naturalism would face no serious challenge. However, probably in infancy – and certainly soon thereafter – everyone comes face to face with experiences that are neither everyday nor moderate, and the intensity of which throws open a persistent world of questions.

There are two forms of such experiences:

1) We may encounter an overpowering joy, a jaw-dropping exhibition of beauty or a fleeting glimpse of unworldly and mesmerizing glory. Such occurrences fail to find easy welcome in the concepts of our minds, or credible utterance in even our most vaunted language. It may have been a sunset, the bewildering and enchanting mystery shining from the face of a small child, a rush of inexplicable well-being, or perhaps a serious listen to Berlioz’ Te Deum – whatever it was, it lifted us briefly into a strangely busy factory of dreams. We found ourselves, if only for a moment, accompanied by a surge of crazy hope and anticipated bliss, all of which the passing phenomenon seems unable to account for.

2) Of course, an opposite visitation may come from the other pole. It may have been the gut-wrenching news of the death of a loved one, or the witness of the cruelty of an incurable disease ravishing someone’s body, or a news report on the civilian victims of warfare, burnt and deformed by the horrors of the modern science of death.

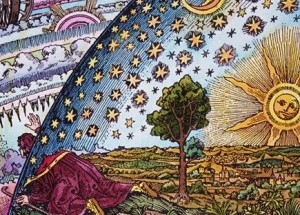

Whether happy or horrific, we all know those moments when something out of the ordinary befalls the small circle of our lives. Furthermore – and this is what begins to shake the foundations of materialism – we instinctively feel that our immediate world seems an unlikely mother of such marvels and monstrosities; it seems instead that something beyond has just intruded, producing a fleeting episode of noumenal ecstasy or fiendish horror.

These invasions are experiences of what we might call the “antipodes of transcendence,” that is, the two extreme apertures through which uncommon energies penetrate our world. They bring an unequivocal message of something more. We find ourselves torn and challenged by two preternatural extremities: something exceedingly evil that fills us with abysmal dread, but simultaneously positions itself as the uncanny counterpart to all that is overwhelmingly good and breathtakingly beautiful, and that enthralls us with bliss. Admittedly rare, but all the more unmistakable for that very reason, these experiences punctuate and mystify our otherwise “everyday” existence. It is our world’s ability to accommodate the cohabitation of these unlikely accomplices that convinces us that something unworldly is afoot.

When we witness the real and troubling existence of an unrepentant murderer, and then the equally obvious existence of an almost thaumaturgic saint (perhaps a Charles Manson in the first case, and then a Mother Theresa in the second), we notice an unexpected but unmistakable similarity: both breathe the air of another world. But the two worlds from which their singularity draws sustenance have in common only their transcendence – the one, a bottomless pit of suffocating negativity; the other, a towering summit of radiant being.

Dante wrote his Divine Comedy about those domains, but anyone with a human heart can take note of their brief epiphanies in even the most modest of lives. This, then, is the ultimate discomfiture of naturalism and materialism: that our natural world continues to have its transparent moments. From time to time, we are allowed temporary peeks into perpetuity. No life can be meaningful that fails to ask the question: Why “on Earth” do these moments exist?