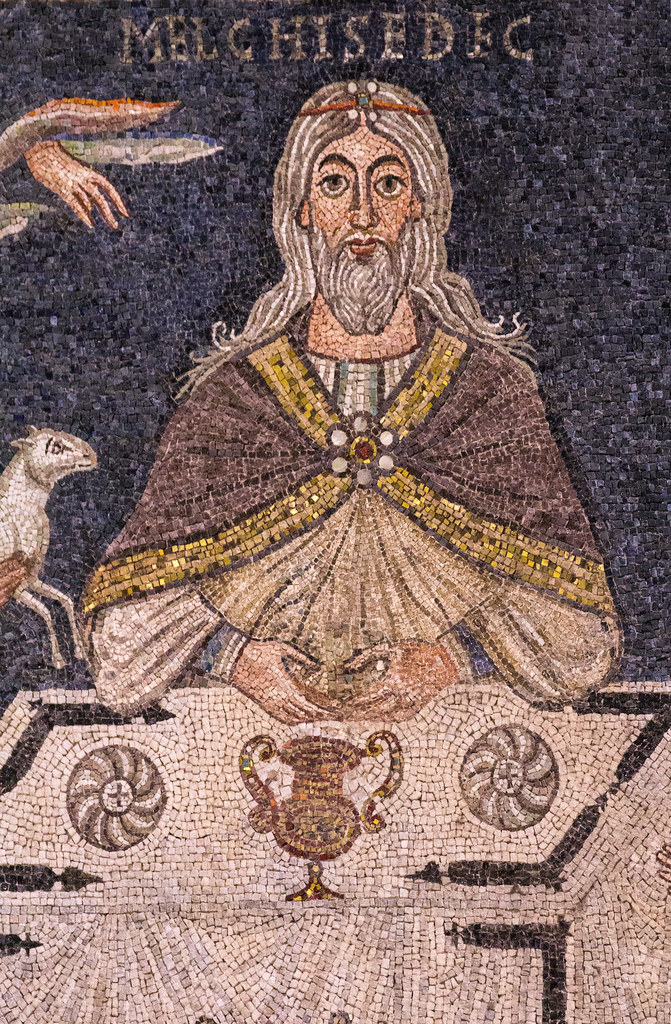

Two seemingly peripheral figures in the pages of Scripture look somewhat enigmatic when viewed separately, but begin to glow with meaning when considered together. I refer to the figure of Melchizedek in Genesis and the figure of the Magus in Matthew (usually counted as three or more Magi). In contrast to the two towering protagonists who stand at the origin of the main Old and New Testament stories – Abraham and Christ – these two ostensibly minor figures are subsidiary; members, one might say, of the supporting cast. Still, for a few moments, their episodes in the overall narrative almost steal the show.

No one is more decisive for the whole Old Testament story than the patriarch of patriarchs, Abraham. Three world religions are often termed “Abrahamic” because of the founding importance they give to this man and his deeds. Genesis 12-25 tells of grand occurrences in his life, such as his journey to Canaan from Ur of the Chaldees, his battles with formidable foes, the great Promise he receives, the miraculous pregnancy of his aged wife and the mysterious Sacrifice he was summoned to make but prevented from performing. All of these stand in high profile as we meditate upon the man Christians have come to call the “Father of our Faith.”

From Abraham’s loins will come the Chosen People, and for Christians, ultimately, the Church. Our understanding of him as the great father, the point of departure of the story of salvation, would seem to be compromised by placing anyone else over and above him. But this does seem to happen in a couple of verses in Genesis (chapter 14,18-20):

“And Melchizedek king of Salem brought out bread and wine; he was priest of God Most High. And he blessed [Abraham] and said: ‘Blessed be Abram by God most High, maker of heaven and earth; and blessed be God Most High, who has delivered your enemies into your hand!’ And Abram gave him a tenth of everything.”

No more mention is made of this mysterious figure in the Old Testament. Or almost none. There is an exception in one striking poetic reference in Psalm 110. It is brief, but it blows open the implications of this king/priest who intrudes almost illogically into the Abrahamic narrative:

“…From the womb of the morning like dew your youth will come to you. The Lord has sworn and will not change his mind, ‘You are a priest forever after the order of Melchizedek.'”

Christian theologians have struggled to understand this “order,” this sacerdotal lineage, prior to and thus superior to the Levitical line which still lay in the loins of Abraham. What seemed most logical was to identify Melchizedek as a figure of Christ. However, that can be said of most any holy man in the Old Covenant. And that might have been enough, were it not for what the Letter to the Hebrews, in chapters 5-7, adds to the mystery. Anyone who takes the New Testament seriously will have to give due attention to what is written, for instance, here:

“…He [Melchisedek] is without father or mother or genealogy, and has neither beginning of days, nor end of life, but resembling the Son of God he continues a priest for ever. See how great he is!…” (Hb. 7, 3-4)

Some Hebrew traditions identified him with Shem, son of Noah, whose descendents would indeed include Christ himself. Sounds promising, but unfortunately we know Shem’s geneology all too well; Melchizedek is supposedly without one. Again, some early Christian theologians assumed he was a particularly prominent pre-Incarnational epiphany of Christ himself. But if there is a “pre-Incarnational” Christ at work in the ancient world, this will inevitably open up a number of questions regarding non-Christian religions, most notably the most developed and primordial religions of the East. I, for one, deem these questions worth exploring.

From other quarters, esoteric speculations have identified Melchizedek with everyone from Hermes Trismegistus to Enoch and even Zoroaster. Documents are too scarce to confirm or give the lie to any of these identifications. But their variety does give witness to what everyone senses: whoever Melchizedek was, he was extraordinarily important.

At this point an obvious, but often overlooked fact should be highlighted: the Biblical dramas – from both Old and New Testaments – do not unfold in Europe. From the beginning to the end they occur in the East, or in what is certainly to the east of the region that will one day be known as Europe. Even Eden was “in the east” (Gn. 2,8), and after the Fall, the cherubim were placed “at the east of the garden of Eden…to guard the way to the tree of life.” (3,24) Of course, St. Paul will venture across the Aegean and finally to Rome, but by then the Gospel drama will have achieved its climax. Paul was just a courier of the resultant message. Otherwise, the furthest westward reaches take us only to Egypt – both with the Hebrews themselves before the Occupation and the Holy Family before Nazareth. But few will call ancient Egypt a part of the “West,” however defined.

When surveying the great surges of philosophy and religion that emerged from Greece and Palestine, we often fail to take into consideration the degree of commerce and contact between the eastern Mediterranean and the Persian, Indian and even Chinese worlds beyond. The singularity – indeed, the “exceptionalism” – of both Greek science and art, on the one hand, and Jewish and Christian religion and morals, on the other, is hardly threatened by this. They still maintain their profile against a background of robust east-west osmosis. But the overall significance of the East has recently moved into new prominence due to unprecedented modern Western contact with the vast religious and philosophical heritage of India and China. Research is still evolving into the common legacies and interactive influences between their accomplishments and the Occident.

Genesis tells us that Melchizedek was the “king of Salem,” that is “king of peace,” which could mean a particular place (traditionally identified as pre-Davidic Jerusalem) or quite possibly a supernatural function linked more to the very notion of peace than to urban geography. Perhaps it means both. Whether or not Melchizedek actually hailed from east of Canaan, or was simply an early monarch of what was to become the City of David, the superlatives used to describe him suggest he hails from the fountainhead of all religion, “without father or mother or genealogy.” In that sense, he may represent a symbolic East, not unrelated to the “East” of Eden.

When we turn, however, to the Magi in St. Matthew’s Gospel, we stand clearly before representatives of the geographical Orient. Countries as diverse as Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Iran and even India have claimed these gentlemen as their own. As always happens with world-changing but mysterious events, traditions and legends have grown apace, with the number of the Magi varying from three to a dozen or more. Some will locate the current resting place of their relics near Tehran, others in Cologne. They’ve been given names (Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar) and grown into integral protagonists in the manger scene each Christmas. Consensus tends to identify them either as Zoroastrians from Persia, Chaldean astrologers from Abraham’s original home or even Nabataeans. Back then, at any rate, astronomy and astrology were so interlocked that any separation of the movements and the meaning of the stars was unthinkable. The behavior of some of those stars indicated that a king was to be born in the west.

These Oriental outsiders were allowed to see and venerate the Messiah before a single Pharisee, Sadducee, Scribe or Priest of the Chosen People could even get close. And the visit of these men from the East would unwittingly cause the Holy Family to move west, to Egypt (provoked by Herod’s Massacre of the Innocents). Decades later, St. Paul would also go west, but the Apostle St. Thomas would go east, all the way to India. With him, followed by subsequent waves of Syrian missionaries, Christianity would bring its graces and grow in Asia long before ever becoming a European religion.

Later Portuguese, and other European missionaries would change that, of course, and the crucial contributions of St. Paul and then of Greek philosophy and Roman law would enter instrumentally into the formulations of Christian faith and the organization of the Christian Church. But in the East this would only come after more than a millennium of Asian Christianity had told its story to eternity. The now often forgotten Christianity of the East, together with its legacy, is at least as important as the one we Westerners identify as our own. Both Melchizedek and the Magi may have a lot to teach us if we have the good fortune of meeting them in the afterlife. *

* The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age, by Philip Jenkins (HarperOne, 2008) is a good guide to what we have forgotten.