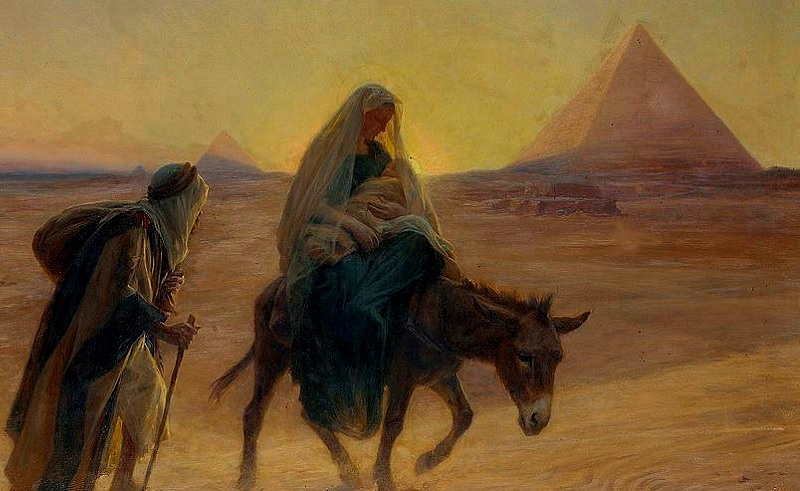

Each time we celebrate the Feast of the Holy Family, I am reminded of my trip to Egypt, several years ago, and the visits I paid to a few of the multiple Coptic Christian sites dedicated to that Family. The Flight to Egypt (mentioned only by St. Matthew) does receive some attention in Christian art, and counts as one of Mary’s Sorrows in the Catholic tradition. It is otherwise somewhat overlooked in the Western church – at least if one is to judge from the prominence it predictably achieved in Egypt. No less than 14 Egyptian sites commemorate that momentous visit with chapels or churches. These mark the resting spots or temporary abodes of the Holy Family as they followed that other Joseph who had also entered Egypt against his will, one and a half millennia before. In due course, the new fugitives would also leave the Egyptians behind them, as Moses had. This time, however, they would not be in search of a Land of Promise, but rather be carrying the Promise with them, in the Child Jesus.

The sweet peace of the manger scene can lull us into a deceptive comfort. We all love to “be home for Christmas,” but the occasion of our holiday is the commemoration of a homelessness of the most cruel variety. In our domestic manger scenes, the dirty stall with its smelly animals that we festoon with colored light only served as a brief and temporary shelter for these three fugitives. We easily forget the turmoil that followed upon the unexpected pregnancy, and the massacre of innocents brought on by three Eastern star-gazers who only asked for directions to Bethlehem. The Family’s years in Egypt – the Copts count seven – like the four centuries of the long sojourn of their ancestors, must have been more formative than we tend to imagine.

Jesus would have begun to talk in the land of the Nile, and some of the first sights caught by his boyish eyes would be pyramids and pharaonic temples. When security permits, today’s tourists love to admire Egypt’s exotic monuments and marvel at this culture that has sired an entire modern science (Egyptology). But for Mary and Joseph it must have been more foreboding than fascinating. What thoughts must have gone through the mind of the boy Jesus as his young memory was stocked with these images of the mysterious land of the pharaohs. And yet, somehow it all makes sense. As the Jews became a people in Egypt, and the Old Testament became a book in Babylonia, here too it seems that God often does his “best work'” when his chosen ones are in exile.