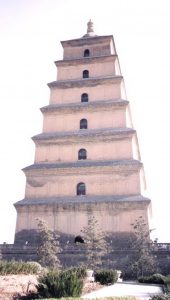

After making my way from Beijing, Mount Tai, Qufu and Harbin in the east of China, I took a plane to one of the country’s former capitals, Xi’an. This was home to the massive translation project which taught Buddhism the Chinese language. That was in the mid-centuries of the first millennium A.D. I had come to East Asia in 2004 to take a look at Taoism, Confucianism and Chinese Buddhism in situ, and Xi’an offered much to supplement what I’d already visited in the eastern regions. However, after exploring the Wild Goose Pagoda (site of those revolutionary translations), a couple of museums, and the fabled Terra Cotta Army of the first emperor, I noticed a curious recommendation in my guidebook: “Forest of Steles.” I decided to take a look.

Long before the hard disk there was the hard stele, a technique of information storage which may outlive google. This was an 11th century emperor’s method of preserving important texts, images and calligraphies of his civilization, not on bone, tortoise shell, parchment or even China’s famous invention of paper, but instead as characters chiseled on huge slabs (“steles”) of granite. As I wandered around the forest among what looked like thousands of black tombstones with myriads of cryptic epitaphs, I recalled Luke 19, “…even the stones will cry out.”

Here the proud legacy of China has done its best to enter into as near a form of perpetuity as possible. But upon concluding my visit, as I re-approached the front gate to leave, I noticed a large stele to my right that I had somehow overlooked upon entering. The brief English title read: “The Nestorian Tablet of the Tang Dynasty.”

I later learned that Nestorian Christians had arrived in China not long after the Buddhists, and that this stele had been crafted in the 8th century. It was then buried in the following century during persecutions of Buddhism and other foreign religions at the end of the first millenium. The stele was dug up in the early 17th century and it was Jesuit missionaries who helped to interpret it. At the turn of the 20th century, efforts from abroad to appropriate the stele for a Western museum made the Chinese promptly seize the artifact and put it out of reach. They placed it in the “Forest.”

This site was soon to become a national treasure of the people that call their country the “Middle Kingdom,” and destined to survive even the devastation of Mao’s Cultural Revolution of 1966-76. It is an oddity of history that this native collection of China’s very own wisdom and religious tradition – which, curiously does not display a single Buddhist inscription – does prominently exhibit a Christian stone manuscript at its very front door. Some sources report that Christianity is currently the fastest growing religion in China (apparently spearheaded by Pentecostals), and if present trends continue, it could have the largest Christian population of any country of the world by 2030.

No less than the fictitious monolith in Space Odyssey, the Nestorian Stele – a documented intrusion of the alien but persistent Christian message – may have triggered a genuine shift in the Chinese adventure, and forecast a new center to an old middle.