Carl Sagan (1934-96)

Humility is easily the most basic of the virtues, as charity is the highest. They are similar, however, in one thing. Both must display their acts with a self-forgetfulness and spontaneity that is spoiled by any semblance of design. The words “I love you” ring hollow unless they emerge from the mouth as naturally as a breath, and the only true proof of humility is the alacrity with which we field unforeseen humiliations. My concern here is with recent emphases on the smallness of our earth and what seem to be poses of cosmic humility.

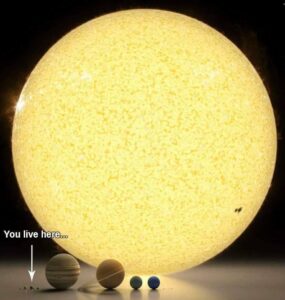

We continue to view the spectacular new images offered by the James Webb Telescope. Besides the profound misapprehensions I referred to in an earlier post, we are now being lectured to by multiple volunteer commentators (especially on social media). They go on and on about how teeny-weeny and itsy-bitsy our little Earth is and how humongous and immeasurably grandiose the cosmos is. These sermons on the Supremacy of Quantity are often illustrated with diagrams like those below (the first a photo taken, apparently, by one of the Voyager space probes launched in the 70s, presently in the outer regions of the Solar System; the second, a quantitative, comparative juxtaposition of the proud bodies of that very system):

It has always intrigued me that in order to express incredible size, we inevitably resort to a parade of zeros. (Are those round little symbols of nothingness trying to tell us something?) Our imaginations, for instance, are totally incapable of even approximately imagining a light-year, but we convince ourselves that we understand it perfectly well when we trot out that sequence of ciphers and proclaim that the light-year is about 6,000,000,000,000 miles long (give or take a few million). Of course, there is nothing wrong with these calculations, and in the proper context, nothing wrong with the comparisons depicted in the two images above and the impressions they have on our imaginations. As always, the problems occur when we ask what all of this means.

What can it mean that there is a huge number of this or of that, or that something is incomparably bigger than something else? Does mere quantity necessarily have the last word in everything? If I have a small diamond and add to it a dozen granite pebbles of the same size, does the diamond lose value? And what difference does it make if I add a hundred, a thousand, a million, or 6 trillion pebbles more?

The trouble with interpreting vastness or multiplicity as equivalent to value dodges the issue of what it is that is vast, or numerous or ‘greater.’ Yes, we are now looking at the universe from our comparatively small Earth. But is there any evidence that the universe is looking back at us? Despite the wishful philosophizing in some universities (where a few academics are now romancing the idea of pan-psychism), we have no evidence at all that the cosmos ever will, or ever could reciprocate our queries. Sci-Fi is loads of fun, but the science in this case is ultimately sobering.

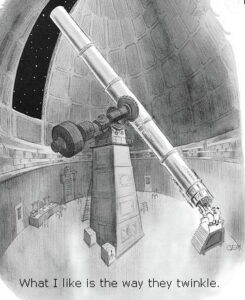

We should marvel indeed at the cosmos, look gratefully at the confected infrared images of the new telescope, but still find nothing more wonderful than gazing, with naked eye, at the vault of stars above our head. That view means immeasurably more than pop-science rhapsodies that try to intimidate us by bigness. In the only world in which we live and move and have our being, size truly doesn’t matter.

A familiar quote from the Pensées of Blaise Pascal:

“Man is only a reed, the weakest in nature, but he is a thinking reed. There is no need for the whole universe to take up arms to crush him: a vapour, a drop of water is enough to kill him. but even if the universe were to crush him, man would still be nobler than his slayer, because he knows that he is dying and the advantage the universe has over him. The universe knows none of this.”

Charles E. Martin, New Yorker, Sept. 3, 1966