A flame is a thing. That’s why we give it a name and can point to it. The same can be said of a river. But, of course, what these two things actually represent are two kinds of embodied change. If the flame were to stop flaring, or the river stop flowing, each would cease to exist. There would be nothing left to point to with your finger, or to be christened with a name. But these incarnate movements, by virtue of their fluid steadfastness and mysterious sameness in change, positively invite our languages to label them and our fingers to point them out.

Our bodies are things too. However, the complexity and intensity of the changes occurring each moment in the depths of our trillions of cells is mind-boggling, to say the least. Before all the other motions we make in the course of a day – walking, talking, gesticulating, eating and fretting – our metabolism is, no less than the leaps of the flame and the flow of the river, the constant dynamic undergirding of our being. For we are alive, and to live is to change. But change does not mean chaos. Behind the cosmic curtain, Heraclitus and Parmenides are secretly holding hands.

Even when we point to things less obviously in motion, such as mountains and the firmament of “fixed” stars, we are told by geologists and astronomers that these too are in flux. Give a few million years and the stars will start flaring out like spent candles and the mountains flowing like rivers.

But what about ideas? Didn’t Plato make a convincing case? He taught us, after all, that the ultimate object of our intellectual pondering are Forms, or Ideas, permanently rooted in a transcendent reality immune to the material world’s processes and evolutions. Isn’t triangularity forever three-sided, redness forever the color we all know and love, and justice the permanent willing that each receive their due? Doesn’t cosmic flux inevitably point to an eternal and transcendent immutability?

Here we must be careful. Stability sounds wonderful, but petrification does not. Even the Christian version of our ultimate beatitude as the face-to-face vision of the eternal and immutable God would morph into a nightmare if it involved the freezing of our mind in a rigid stare at an unflinching divine statue. In Dante’s Comedy, the one who is frozen in immobility is not the saint in heaven, but Satan in hell. Paralysis lies at the cold bottom of hell, and not in the luminous and thermal regions of heavenly bliss. As Dante ascends through Purgatory and up into Paradise, the unmistakable token of that ascent is an increase in mobility and spaciousness, an opening up to more and more freedom and a regaining of the hitherto forfeited “good of the intellect” (il ben dello intelletto, Inf. III, 16). Being “established” in grace is not equivalent to being hogtied, but rather to being unshackled and directed onto the right track. On that path, and only there can we move forward by fully unfolding our powers.

Ideas, like organisms, are alive. They do not move biologically by metabolism, or physically by exchanges of mass and energy, but they do “move.” The correct word for the movement of ideas, however, should be activity, for minds and wills act without material motion. The ideas we have, the judgments we pass, the convictions we hold, the choices we make and every other intellectual or volitional act we perform, all are living realities. They are just as alive – actually far more so! – than the busy transformations occurring in the factories of our cells, or the efforts we make with muscles and bones as we move about the world. Ideas are more interactive than even chemical or nuclear reactions.

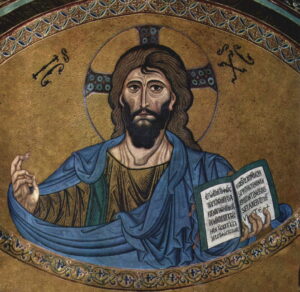

Theologically speaking, all true ideas (as all truths of any sort, intuitive or inferential) lie permanently secured within the infinite wealth of the Logos, which is the second hypostasis of the Holy Trinity. That Logos, being God Himself, never changes; however, it lives with a dynamism and multiplicity of possibilities far beyond human reckoning. We can only achieve a minuscule and approximate assessment of that cornucopia of truth by “moving” our mind from one aspect to another, one perspective to another, one point of entry to another. Later Jewish and Christian thinkers (from Philo to Origen) will locate Plato’s world of Ideas in that very Logos of the Eternal Father. In Christian conviction, this is the Second Person who became man in Christ – who not only speaks words of wisdom, but is the ultimate Word of Wisdom, written in the accessible script of a human nature and an historical story.

Thus, the unity and endurance of true ideas is rooted in an abiding reality indeed. But the important point to grasp here is that truth lives. The unceasing activity of its contemplation – taken to the nth degree if the object of that contemplation is the infinite, living God – does not abandon its foundations, but stands upon them in order to view new connections, new implications, new consequences and new sister-ideas. This is what Newman meant by the development of doctrine. In living things change is designed to move in lockstep with the exigencies of a stable nature. A young puppy and an aging old dog are quite different to the eye, but are both quite canine. Our idea of the “cosmos,” born in Greek myth and philosophy, is still with us, but what we understand the cosmos to be has changed considerably. Still, it’s the same place.

What happens to ideas in time is that they grow. Their facets, like those of a diamond, sparkle in different directions as they are turned. What an idea presupposes, what follows from an idea, and to what other ideas it is actually or potentially related – all these dimensions reveal themselves over time. But the ideas develop not by ceasing to be what they are, but by becoming ever more fully what they are, disclosing a world of relations only dimly grasped when they were first launched in the human mind.

Despite its fidelity to an original source, each idea is not just “conservative,” but simultaneously innovative, for there is nothing it conserves more faithfully than the dynamism of its adaptation to the Truth in its totality. When Christ said, “I am the way, the truth and the life” (John 14,6), he wanted us to know that there will always be growth and discovery in our journey into God, and that it is not merely a matter of well-defined formulas and well-honed arguments (as important as they are).

He wanted to remind us that truth lives, and that what lives grows. A way is walked, and not just plotted. And truth, like all living things, shows forth that hallmark of all life: fecundity. Goethe said: Was ist fruchtbar, das allein ist wahr (‘Only the fecund is genuinely true.’). That fecundity is a mark not just of something, but even more of someone. Christ wished to reveal that the Truth, in the final analysis, is personal, and that it is only in his Person as the Logos of the Father in the Holy Spirit that we find the ultimate home of all ideas, the trembling fountain of all doctrines, and the consummation of all discourse. Every idea, every truth and every item of knowledge is softly whispering: “in the Name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.”