How often do we hear that over 90% of this, or 95% of that, or even 99% of something else surprisingly dwarfs the remaining percents in the calculation, and that our world and our lives seem to get almost squeezed out of existence in their appointed share of reality? Are we really living in that little blue slice of the pie in the picture above? Take a look at some of the stats:

99% of the space of the entire cosmos is empty.

99% of every atom is also empty.

More than 95% of the world’s ocean floor is still unmapped and the life forms that inhabit it largely unknown.

Over 90% of all the living cells in our body are not human (…not to leave this one hanging in the air: they are microorganisms).

Over 95% of the extant matter in the cosmos has hitherto escaped our analysis (so-called ‘dark energy and matter’). All our vaunted knowledge of material reality is about that remaining 5%.

99.9% of the history of the universe had already spent itself by the time we humans came onto the scene.

Over 99% of all the visible matter in the universe is neither solid, nor liquid, nor gas (it’s plasma).

99,5% of all the species that have ever existed on earth are extinct.

Well over 90% of our genetic material we share with other primates, and most of it even with lower life forms.

(There are some others, but I think that will do.)

There seems to be very little entity left over after these statistical genocides. Moreover, such statistics tend to be used by the purveyors of scientism as means of divesting our human experience of meaning, value and purpose. We are, they repeat mantra-like, just a teeny-weeny speck in the immeasurable vastness of space; just one more animal, one more mammal, among all the other products of random evolutionary throws of the dice, differing by only a slender sliver of genetic information; and our so treasured “world” is actually just so much empty space, patterned upon empty atoms and empty galaxies, sporadically sprinkled with transient molecules and lonely stars; and the fact that our life form is still around is at most just good fortune, since almost every other species has long since vanished, and the ones still with us may not be around for long.

Modern mavens of the supremacy of science love to wow us with these quantitative boasts. But they are, as usual, misguided. Consider the following: If I have a hundred pebbles and only one of them happens to be a diamond, its 1% status in the pile of gravel hardly compromises its value. And one sound philosophical observation about the claim that atoms and cosmic space are predominantly empty would be to note that neither of those perspectives are actually relevant to living a human life. Leaving the empty macro- and microcosmoses to the astronauts and nuclear physicists, we who dwell in the mesocosmos (that is, the surrounding spectacle greeted by our five senses) have a world very full indeed – full of things, people, mountains, rivers, oceans, continents, and marvels in abundance. Read the world’s best poets and you’ll learn about this saner view of reality, for we instinctively know that our world is a full and overflowing cornucopia of very solid wonders.

We who dwell on the humble Earth are actually eager to see pictures of the deep sea creatures yet to be found, as we also greet every new butterfly or lizard discovered in the Amazon. We rejoice in the ocean of microbes that our human tissues swim in, grateful for their contribution to our well-being and happy to be in the cellular minority. That the scientists still call 95% of the cosmos dark stuff (that is, unknown) seems to us a salubrious humiliation in the face of their often over-preening declarations of the past. And that most of the species of earth have already passed into history we find astonishing indeed, so rich and various are the countless few that still parade before us.

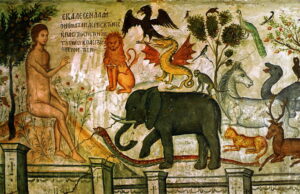

It hardly matters that most of astronomical and geological time is behind us (where else could it go?). The story of our remarkable race continues to be extraordinary, whether its time on earth has lasted half an everlasting aeon or just half an hour. And – to return to the diamond – if we have only a small portion of exclusively human material in our genetic mix, that modest handful of DNA is about as valuable and momentous as a diamond among the pebbles, or of a uranium atom in an A-bomb. All of this only reminds us of a lonely Adam looking out at an endless zoo, awash with wonder at a vision only Infinity could have fashioned.