The crucifix is an image; the cross is a symbol. The distinction is not academic. When we compare the imaginative universe of Islam and Hinduism, for example, we find in the first instance a tradition that is wary of images, and for the most part prohibits figurative depictions of sensory creatures in any shape or form; indeed, the higher they are in the hierarchy of life, the less are their images tolerated – humans far less than brute beasts, and holy humans (say, Moses, Jesus or Mohammed) least of all.

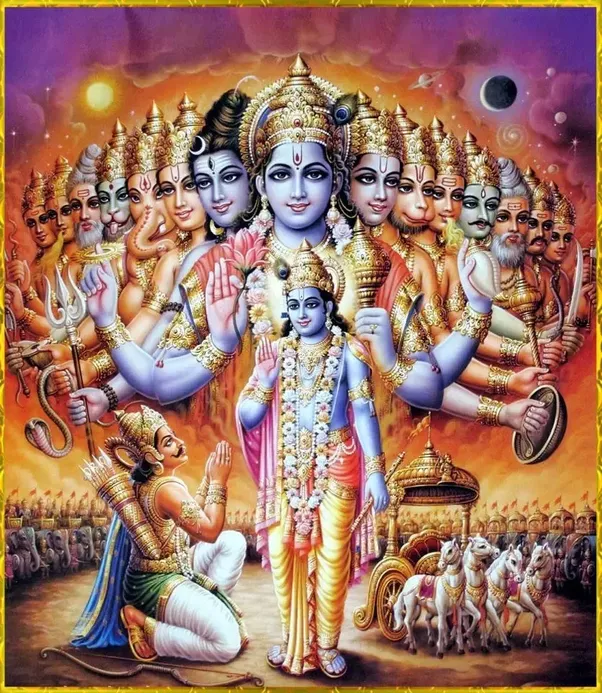

In contrast, the complex religious tradition of India seems to breed a jungle of images, and the high and holy get more than most. Still, if we are to be exact (and perhaps a tad academic after all), the Hindu world’s statues and pictures are not really images at all; they are symbols. At the risk of oversimplification, Islam would ideally ban all images, and only allow vegetative and calligraphic ornamentation; Hinduism, on the other hand, could conceivably accept any and all images, but only under the whispered condition (shared among the wise) that they are nothing more than symbols.

The image (the ‘icon’) re-presents something absent by way of similarity (a portrait, photo, etc.); a symbol only suggests or vehicles something, but something so large, complex or mysterious that similarity cannot be obtained (liturgical colors, a church spire, a country’s flag, etc.). There are important intersections and overlappings of the two, but we shall remain here within the problematic of the basic distinction.

![]() Now there are rather transparent metaphysical reasons why Islam is in principle “aniconic” (unfavorable to images), and Hinduism profusely iconic. The devout Muslim, resolutely intent on affirming the uniqueness and unicity of God, fears that distance between image and idol could shrink to near coincidence when higher creatures are made object of a figurative imitation.

Now there are rather transparent metaphysical reasons why Islam is in principle “aniconic” (unfavorable to images), and Hinduism profusely iconic. The devout Muslim, resolutely intent on affirming the uniqueness and unicity of God, fears that distance between image and idol could shrink to near coincidence when higher creatures are made object of a figurative imitation.

He espies here two lurking temptations of committing shirk (the attribution of divine qualities to a creature): 1) by the very act of producing a simulacrum of animals and men, you could fall into the error of fancying yourself a divine Creator of life; and 2) the work of art thus produced will most likely mislead at least some into adoration, and you will have fashioned an idol. Contemporaneous in time and almost coterminous in problematic were Christianity’s own struggles with the matter of icons, but its theology would impose a unique solution, as we shall see.

Students of Indian thought are well aware of the looming notion of maya, a conceptual lens through which one sees the material world as being: 1) in a dark sense, a dance of forms that pretends to be what it is not and thus provokes ‘illusory’ states of consciousness, or 2) in a deeper and more luminous sense, the very ma-gical and ma-terial play of true reality – those two ma‘s are both Indo-European cognates of the one in ma-ya – and thus capable of being its vehicle to the properly purified eye. But however one interprets the word, the Hindu sees the world not only as contingent in the Western sense (something that is but could also not be), but equally, and more innately, as a permanently morphing, gossamery appearance in forever changing continuities and discontinuities with absolute reality.

The gods themselves (as various forms of Ishvara, the ‘personal god’) emerge and submerge as fugitive faces of this or that aspect of Brahman. Some of them even ‘descend’ as missionary avatars (Rama or Krishna, for example), penetrating into the lower, denser regions of maya to be of service to those struggling to be freed of its ceaseless, pointless flow (samsara). But for the Hindu, that flow, symbolized by the Dance of Shiva, has gone on forever and will never, can never end. It is, after all, what the universe is.

Christians share with Jews and Muslims the belief that the world is the result of an irreducibly and metaphysically personal and free act on the part of God – free not in the sense of a choice, but in the sense of a complete absence of constraint – and that the whole creation is therefore particular. The Almighty could have created any number of other, very different worlds than the one we live in – and may have even done so – but we obviously live in this one, and accordingly, are related to God in a very particular way. For the Abrahamic faiths, the world is not an endless play of forms, but rather a book one is invited to read, a message one receives, a very specific cosmos (with an exact speed of light, for example). For these Semitic faiths, the cosmos is not a perpetual and unending manifestation of all the possibilities inherent in the divine infinitude, but rather one possibility among many, and one very heavy with meaning.

Historians of science have often puzzled over why modern sciences (with all their blessings and all their curses) only arose in a Christian, European milieu. But it is probably that very Biblical conviction about creation that made the scientific approach to the cosmos possible to begin with. If the world is not in any way contiguous with God, a part of God, God ‘inside-out’, or a co-equal emanation of the divine being, but is instead quite distinct and particular in relation to its Maker, modern science becomes possible. Investigating the world of mass and energy and disclosing its physical laws can no longer be proscribed as the violation of a sanctuary, but seen instead as the logical response to the very logos-laden universe spread out before us. Such a universe is understood indeed as expressive of God, but in the very ‘local’ language, so to speak, of a very specific world.

![]()

All of this specificity gives to a cosmos that is most definitely contingent also a high measure of reality, however dependent on the God who made it. The meditative Hindu will ultimately be driven to see everything – even himself – as a fleeting symbol of the Absolute. He will sometimes be logically led to view his only destiny as something like a dissolution into that solvent matrix. The Christian, in contrast, finds his individual personhood and that of the God who created him to be quite solid and abiding poles between which life, knowledge and love can flow, the poles expanding but never changing in substance.

Despite all this, since the particular world also necessarily manifests the mysteries of God in its every detail, symbols will continue to play an important (though not central) role in Christian faith, as they do similarly in Judaism and Islam.

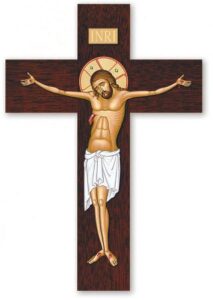

In Christian tradition in particular, there is no shortage of crosses as symbols of the Redemption, of Sacred and Immaculate Hearts as symbols of love and purity, lifted arms as gestures of prayer, and liturgical colors and vestments suggestive of an ever-splendid background to the sacramental mysteries. All these are like a divinely designed symbolic foil to the very real gems of the divine presence, or – switching the metaphor – an orchestral accompaniment to a soaring tenor.

That tenor, however, is singing a story. Sovereignly above and beyond all this sea of symbols are the pictures: from the Manger Scene and portrayals of Christ in miracle and word, to the ultimate images and icons of the Crucified Savior and the Empty Tomb. These are not symbols suggesting transcendent verities or values, but depictions of historical facts that tell a story in which God touches the world in a way unknown to the Vedas and the Gita, the Sutras of the Buddha, or even the Torah and the Qur’an. It’s what puts the ‘new’ in the New Testament, and plants a ‘sign of contradiction’ (Lk. 2,34) in the course of human history.

Christian belief in the Incarnation – and in its train: the Resurrection, the sacraments and a transformed but still very physical New Jerusalem – means that out of the ambiguous and shifting world of indirect symbols, something unprecedented emerges and eventually sets symbolism to one side: here instead are the faces and deeds of the Paschal Mystery, which step forth dramatically, grab hold of the cosmos and enter deeply into the mystery of time, and do all this with a transcendent grip that shakes them to their core. The result is a concrete and unforgettable scenario of images. These depictions will become Christianity’s most characteristic imaginative language.

In 787, the last of the Church’s first seven ecumenical councils will be held. It will poise the world of Christian art squarely, though delicately, between the iconoclasm of the Muslims and the symbolic exuberance of the Hindus. But it does this by affirming the free act of the personal God who took hold of his own creation and became one with it in the womb of the Blessed Virgin. That act and the resulting facts will produce a world of architecture, painting and statuary that does indeed dip freely and creatively into a palette of traditional emblems and symbols, but only in order to better frame the mysteries of the Word Incarnate. Its unbreakable bond with the created universe will make that universe into God’s permanent dwelling place.