In the picture you see my father, wondering why his oldest son is taking a snapshot of a supermarket row of breakfast cereals. I’ve seen longer rows than this, but this one serves to document one of contemporary culture’s most familiar cases of overblown ‘freedom of choice’. I might have used flavors of soft drink, models of automobile, styles of T-shirt, or even themes of website to make my point. About this last: if WordPress had offered me a choice of three or four themes to frame my site in, I would have promptly chosen the simplest one and gotten on with my blogging. As it was, I had to surf through nearly 200 different themes, weigh their comparative merits, and spend almost an hour narrowing it down to the one I finally chose (even then, the sap was sucked out of my victory as I continued – and continue – to wonder if I should have chosen another theme that might have been even better). But at least I was free to choose! Or was I?

Many will have heard of a famous 1950s lecture by the philosopher Isaiah Berlin on ‘two concepts of liberty’ in which he highlights two ways of speaking of freedom which have become well-known ever since: one, freedom from; the other, freedom for. It is still worth reading and the distinction is important. But far more important is another distinction which is promptly lost from view as we fret over choosing between Mini-Wheats and Froot-Loops. It is the distinction between the classical, medieval understanding of freedom as the progressive unfolding of our natural faculties under the guidance of reason and the optimization provided by virtue, and the reigning modern notion of freedom as the ability to choose, and then to choose again, and then again — the idea of an autonomous, undetermined, monadic individual entitled to survey a potentially infinite spectrum of options and select the one most coveted.

The traditional ideal is best imaged by Dante. He sees it as a man ascending aloft and away from the thick suffocation of the bogus ‘freedom’ represented as Satan at the compressed heart of hell, immobilized in the ice of his own choice of self over reality. True freedom moves upwards through the ordeals of purification, and opens like a flower to an ever-expanding sky of air and light. The power of the virtues opens, expands and flexes the faculties they perfect, carrying them to a state of full deployment.

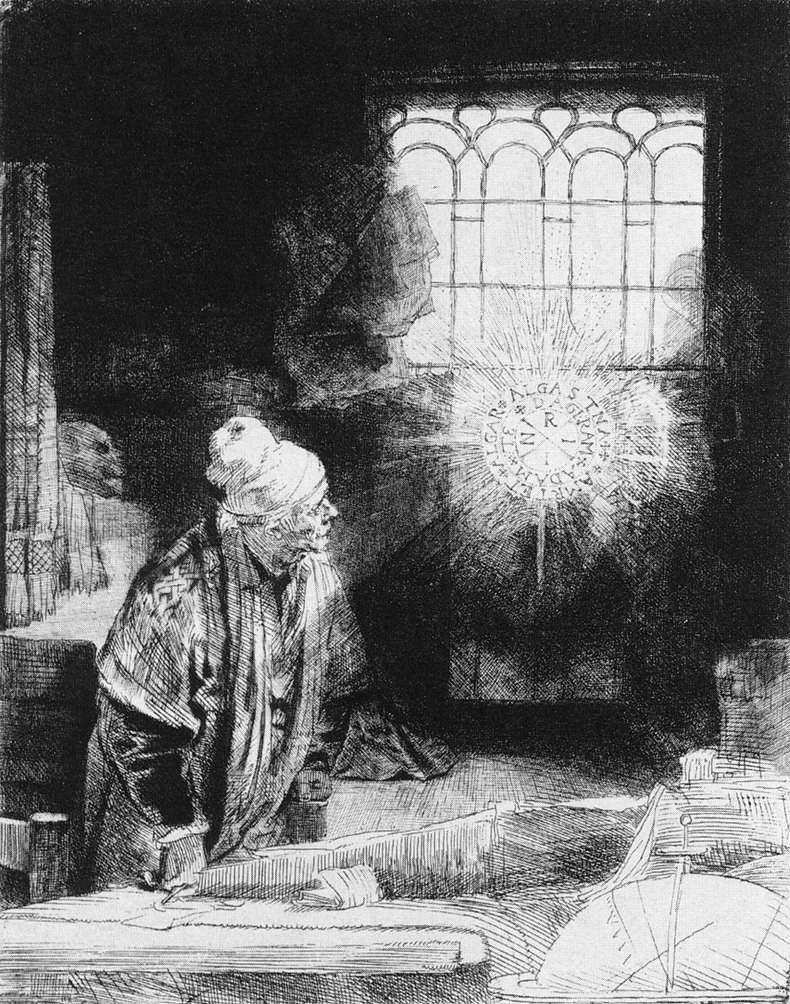

In contrast, the modern icon of individualistic liberty is the cognitive control-freak Faust, focused painfully, and obsessively, on choosing the mastery of knowledge over all else. The mantra here is: knowledge is power, power over nature, over time, and finally over reality. This he purchased at the price of that very soul which Dante would lead heavenwards to bliss. Faust’s mind and heart instead are squeezed to one lone and painful point as he squints at the esoteric secrets that promised light, but only delivered the cold black of the void.

Emancipation from this miniaturized modern version of freedom (with its endless spasms of choice in an addictive fit of arbitrariness), and freedom for a reconquest of the incomparably deeper and broader traditional notion, brings freedom to be (in actuality) all that we are (in potency). Such true freedom can only come to pass when we grow in the powerful virtues of prudence, temperance, fortitude and justice (and for the supernaturally valiant: faith, hope and charity). Otherwise, we will continue surfing cumbersomely up and down endless menus of options and sub-options, in pursuit of some elusive breakfast cereal, or the latest I-Phone, that promises – like a con-man – to transport us to the peace which passeth all understanding.