I love to greet new challenges to my deepest convictions. I ran across one yesterday which kept circling like a vulture in my mind all night. When it finally swooped down for the kill, I was ready.

First, the challenge: One reason to regard religion as a product of fantasy, wish-fulfillment and sloppy thinking, and science as the only trustworthy avenue to truth, would seem to be that science is, fundamentally, one, while religion’s name is legion. Science tends to move convergently toward global consensus, and once a theory of gravity, a periodic table of elements, a discovered black hole – or whatever scientific disclosure one wishes to cite – is sufficiently tested and proven, the unity of the scientific enterprise is once again confirmed.

Religions, in contrast, not only present themselves in multiple self-contradicting camps, but are forever proliferating new sects and denominations like a herd of randy rabbits. What more proof is needed that religion derives not from knowledge of some coherent verity, but rather from the multiplication of human superstitions, emotions and imaginings?

Sounds pretty good, I concede. If one were to stop thinking here – and people usually do – it might seem a slam-dunk. There are, however, at least two serious problems with this simple formula. The first regards the supposed unity of the sciences; the second, the full import of the multiplicity of religions.

First, consider the sciences: I already highlighted in an earlier post (Something’s Missing) the considerable challenge the physical sciences are currently facing after discovering that nearly 95% of their subject matter has hitherto oddly eluded detection. With such a high fever of ignorance, it’s difficult to imagine how any contemporary scientist – despite all their undeniable conquests – can lay claim to full and healthy synthesis or easy coherence. And let us not forget that even the fabled “unified theory” pursued by the great Einstein – hoping to bring quantum mechanics and relativity under one mathematical umbrella (and which involved only the other 5% of material reality anyway) – has yet to find its equations.

Despite the dream of old Descartes that all the sciences could somehow unveil their mysteries through one and only one universal method, they have continued to ignore him and to flourish robustly in the plural. And they do this precisely by applying their own distinct methods, many even maintaining a sort of epistemological autonomy. Science, with its ever-shifting paradigms, may nervously try to corral its multiple data and theories behind a single fence, but it has yet to tender a credible claim to one monolithic body of doctrine. Not even close. Its deepest truths seem, often enough, to shoot in different directions. As Niels Bohr famously quipped: “the opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.”

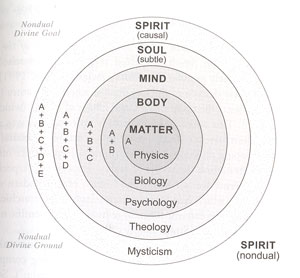

But still, at least we can confidently affirm that religions are – in terms of some overriding unity – hopeless, and irreducibly multiple, right? Multiple, perhaps, but hopeless, hardly. Virtually all religion is predicated on the assumption that there exist dimensions of reality transcendent to the one our senses touch and our meters measure, and that all of that outlying entity is not only vastly more extensive than the physical universe, but also more intensive – more various, heterogeneous and complex.

As each religious tradition maintains that our connection with those higher regions is important, but has also been somehow compromised, it advances ways, techniques, rites or proffered graces by which our communion with those higher worlds can be restored. And since there is multiplicity in those transcendent regions of the real, there will be multiplicity in the way in which this or that religion gains access to them, and indeed which “part” of that world it accesses.

The variety of religions poses challenges indeed to the truth-claims of each tradition, and no one will claim those challenges have already been met. But the multiplicity of faiths and scriptures and clergy and rites and sacraments and all the churches, temples, synagogues, mosques, gurdwaras and pagodas of the world no more prove the non-existence of the transcendence they lay claim to, than the fact that there are thousands of spoken languages in the world proves that there is nothing to talk about.