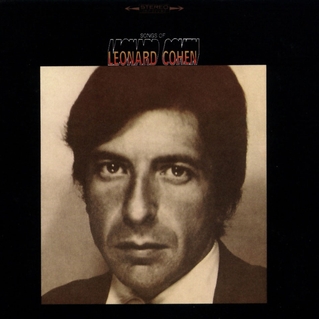

I was at a so-called “rock mass” in Kansas City back in 1967, with a local group playing Jefferson Airplane songs and everyone dancing in the aisles. It was there where I first heard the voice of the Canadian bard whom I would listen to and follow for the next half a century. At one point in the service, the band grew silent and a recording of Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne” was played. The non-commercial voice of the man – on occasion ever-so-slightly off-key – touched me as no other sound has before or since. The simple guitar-work which accompanied it was understated but obviously fitting. I discovered why this Jewish psalmist had earned his part in Christian liturgy as I heard the following lines:

And Jesus was a sailor

When he walked upon the water

And he spent a long time watching

From his lonely wooden tower

And when he knew for certain

Only drowning men could see him

He said “All men will be sailors then

Until the sea shall free them”

But he himself was broken

Long before the sky would open

Forsaken, almost human

He sank beneath your wisdom like a stone.

However theologically inexact, these lines caught my adolescent attention and won Cohen a new fan. That was his first song on his first album in 1967. As he lay dying a half-century later, and after twelve intervening albums, he put the finishing touches on his last songs. Among them was one with these lines:

I wish there was a treaty we could sign

I do not care who takes this bloody hill

I’m angry and I’m tired all the time

I wish there was a treaty, I wish there was a treaty

Between your love and mine

Or, from another late song:

Seemed the better way

When first I heard him speak

But now it’s much too late

To turn the other cheek

(…) I better hold my tongue

I better take my place

Lift this glass of blood

Try to say the grace

Good poetry provokes construal, but good construal inevitably points back to poetry. More is said, and more life nourished, in the tropes of verse and meter than can ever be preserved and pickled in prose. That is why poetry exists. And Cohen was first of all a poet. He only started singing when his books did not bring in the money he needed. As would happen again in his life, such unforeseen constraints brought out the best in him. His music – and his increasingly deep and gravelly voice – become counter-punctual enrichments and commentaries on his verse.

Good poetry provokes construal, but good construal inevitably points back to poetry. More is said, and more life nourished, in the tropes of verse and meter than can ever be preserved and pickled in prose. That is why poetry exists. And Cohen was first of all a poet. He only started singing when his books did not bring in the money he needed. As would happen again in his life, such unforeseen constraints brought out the best in him. His music – and his increasingly deep and gravelly voice – become counter-punctual enrichments and commentaries on his verse.

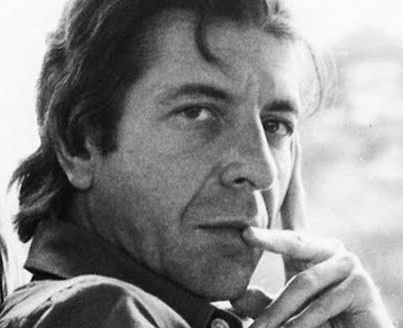

The melancholy of the man – he was plagued by depression during much of his life – turned this alchemy into an acoustic narcotic of such power, some suggested that Leonard Cohen albums be sold with complementary razor blades. That otherworldly voice and the simple but poignant chord progressions could become too onerous for mortal ears. He wrote of death, pain, despair and longing, but also of sex, religion and hope. It’s all there, from his Jewish upbringing and the haunting tales of the Old “Treaty” on to his imagination’s persistent flirtation with Christianity.

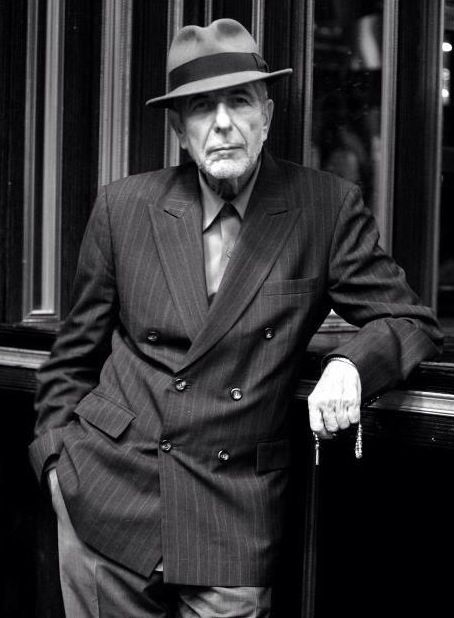

Like Dylan’s songs, Cohen’s would be unthinkable without Old Testament and Gospel references. He talked like a prophet and looked the part as well, an ever-slender gentleman in suit and fedora. As Dylan took a retreat in evangelical Christianity, Cohen sat at the feet of a Zen master for five years; they both emerged from their spiritual sabbaticals changed, if not converted. But awaiting Cohen was an exercise in detachment he had probably not envisioned in his sessions of zazen. As he returned to the world, he discovered his manager had disappeared with his life savings, and despite litigation, the money was gone.

Out of sheer necessity, he tested the waters of popular culture to see if anyone would still pay to see a man, now pushing 80, trying to sing his old songs. It turned out to be the beginning of a spectacularly successful four-year world tour, not only re-introducing him to old fans (like me), but gaining countless new ones as well. More significantly, perhaps, was how this brush with financial collapse and mortification inspired his songwriting, deepened his wisdom and humility, and made him, at long last, comfortable on the stage. His 2008 London concert was almost liturgical. The last four albums could well be his best: Old Ideas, Popular Problems, and his dual requiem testament: You Want it Darker (released just before his death), and Thanks for the Dance (produced by his son and released three years after his passing) – all meeting with overwhelming critical praise. From Old Ideas:

Show me the place, help me roll away the stone

Show me the place, I can’t move this thing alone

Show me the place where the word became a man

Show me the place where the suffering began.