The birth of Christianity is irreducibly, unmistakably and – among religions of the world – uniquely centered around an event. It is, first and foremost, not about a teaching to be learned, an example to be followed or a moral precept to be enjoined (a number of other religions will offer you that), but rather a happening, and one that is both weird and wonderful.

The first generations of preachers of this faith walked the Mediterranean world like men stunned or drugged, almost stuttering their message as they pointed their trembling fingers back to that place and that moment in which something had occurred that changed everything forever. It was the Resurrection – an event which, almost by definition, you cannot understand. The worst thing that ever happened (the Crucifixion) had just befallen the best man who ever lived, and he had answered it with the greatest surprise of history. Not even St. Paul claimed to have figured it out, but he knew that things can happen that do not fit into our customs of thought. This was one of them, and to the nth degree.

As the years rolled by, and that event sunk deeper and deeper into the past, two things happened. First, the eyewitnesses of the Risen Christ soon died, and the event was thereafter witnessed more by mouths and ears than by eyes. But later eyes wanted to see their world redecorated by the new truth, and hear sounds that thrilled with the new message; above all, they wanted to be rescued from our tragic tendency to forget. Thus, slowly but logically, liturgical forms evolved, clerical paraments, chapels and churches, and an explosion of Christian art and music began to fill the world – all to remind us of a glory once glimpsed in a Man whose birthday became the measure of time.

From church walls covered with Byzantine icons in the East to Gothic spires in the West, from almost whispered mantras of Gregorian Chant to Baroque and Romantic musical exaggeration and insistent gesture, from refined high Christian culture to kitschy pilgrimage memorabilia – a new garden of sensations would keep us from forgetting what had happened, crowding our visual fields with unusual light and putting new music into our ears.

For Catholic and Orthodox Christians, the Eucharist – whether called the Mass or the Divine Liturgy – is the event in time designed by Providence to keep the Event of the fullness of time anchored in our shifting world of change. It happens every day, all over the world, and – with the possible exception of the annual Hajj – becomes the most spectacular religious show on earth when a pope offers Mass in public.

Even the secular media cannot resist its magic, though it often trips over itself trying to find the right verb to describe what is occurring. It is amusing to read lines like “the pope did (or had, or performed, or gave) Mass – all expressions I have read in newspapers – as they found themselves at a loss to describe what that ‘thing’ is that Catholics call the Mass, and how one does it. It obviously is more than a commemoration, more than a sermon, more than a songfest, more than a ‘service’ (though service it is); again, it is an event, a happening. And something happens to you when you “go to Mass” – once again, the verbs contend: one goes to Mass, or assists at Mass, has Mass, hears Mass…takes Communion, has communion, receives Communion, communicates, etc.

Verbs have a hard time keeping up with the acts of a God who is the Verb Incarnate. In fairness to Protestants, it must be said that even Catholics tend to get tongue-tied when asked about the details of their fabled ritual. A number of distinctions – regarding sacrament and sacrifice, time and eternity, and a handful of others – would need to be urged in order to account for the rite’s density, which challenges both word and concept. But my only point here is that the liturgy, with all its art and music, produced a conspicuous, worldwide change in time and space and that it was called forth by the event of Christ’s mystery.

That is the first thing that happened after the Happening: liturgy, art, music – in short, a visual and acoustic makeover of our world. The second thing is just as important. As the first generation of Christians feverishly tried to put down in writing what had just occurred, they found themselves creating a new literary category – the Gospel – and adding Epistles, Acts and an Apocalypse into the mix – four genres virtually vibrating with urgency.

All this evolved into the dramatic and insistent little text we now call the New Testament (an expression the Gospels, significantly, reserve for the Eucharist itself). In some ways it is more a set of preaching documents than a tome to be put on a bookshelf. But meditating on those documents and partaking of that ritual Mystery, the Master enjoined subsequent generations to ponder it all – like the disciples of Emmaus, to whom Christ had revealed himself through the Scriptures and the Breaking of Bread.

Thus grew, slowly and incrementally – and contemporaneously with the spreading array of new art and liturgy – a new way of thinking. We call it theology. Here, I only wish to draw attention to one detail of liturgical event and theological reflection. Christians not of the Catholic or Orthodox traditions are often taken aback by the insistence of those traditions on the real presence of Christ – body, soul and divinity – under the Eucharistic species at Mass. There is a considerable body of polemical literature about this question in the history of theology, and I for one find the weight of argument quite convincing on the Catholic and Orthodox side of the debate. But what concerns me here is much simpler, and it might transcend confessional disagreements.

Most who believe in Christ’s Resurrection accept that his body now exists in a way fundamentally different from that of our current ponderous organisms. We read of this in the Gospel reports of his unusual appearances after rising from the dead: passing through closed doors, appearing and disappearing almost like a ghost (and not to forget the refulgent apparition of his glory at the Transfiguration). Christian teaching in virtually all of its mainstream forms agrees that he still has a real body now, but that the matter of that body (and not only the soul) has been ‘glorified’. What that really means we have no way of definitively knowing until, God-willing, we one day partake of it. One thing that it entails, however, we can already surmise.

When Catholics and Orthodox insist that Jesus is really present in the Eucharist, it is to that mysterious and glorious reality of his transfigured body and blood that they refer. That does not imply, however, that the presence is merely spiritual, or symbolic, or metaphorical, etc., or any of the other ways of unduly domesticating the mystery. It is a real body (with molecules and cells), but in a form already anticipating that state towards which we are all called to proceed, grace by grace.

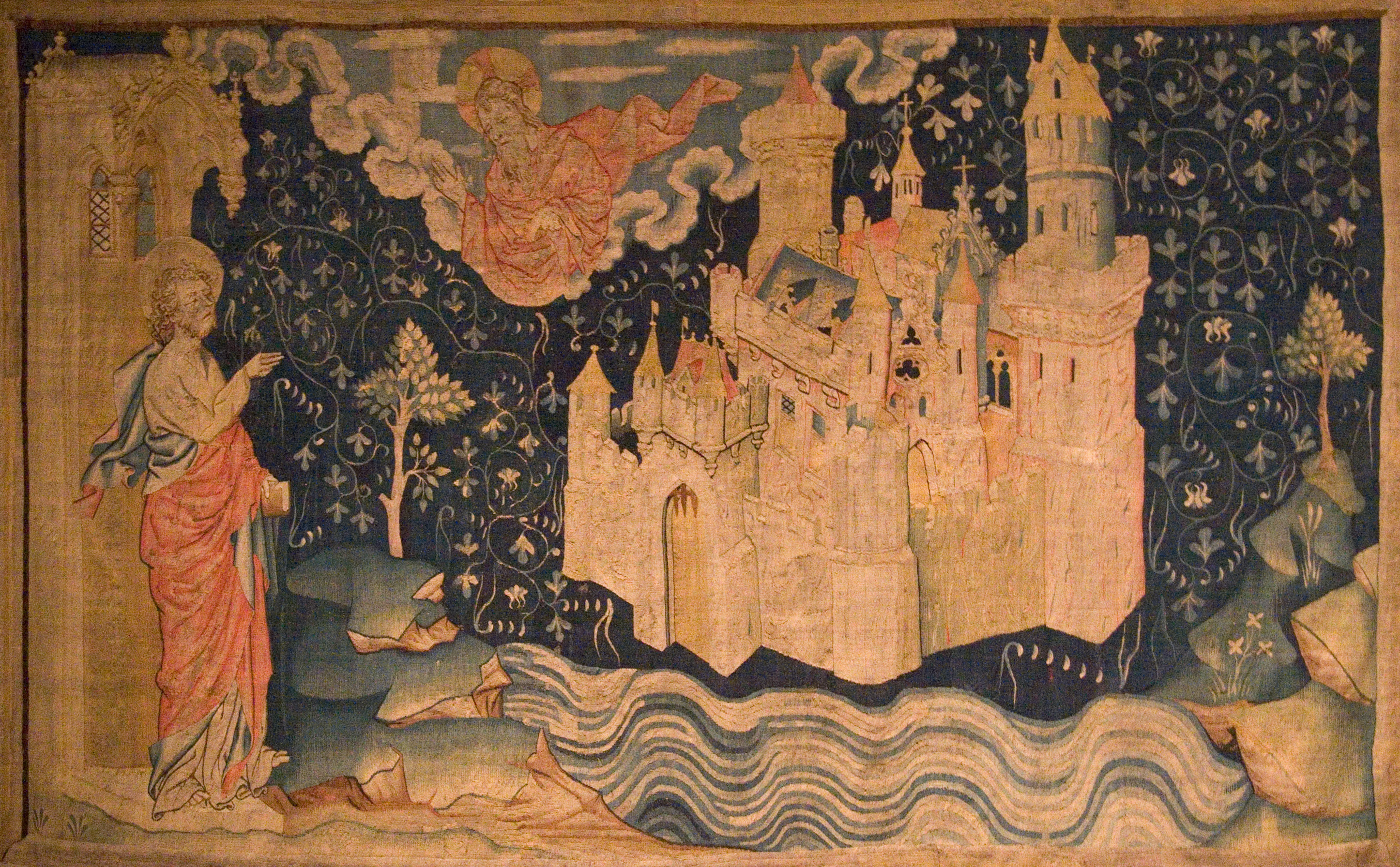

In order to adhere to a traditional belief in the Real Presence, one is not required to imagine an adult male body, such as those we see around us, somehow ‘miraculously’ crunched into the space of a tiny host or a goblet of wine. It is a mystery of faith, not an absurdity of faith. The mode of existence of the glorified human frame of Christ is already a miraculous prefiguration of the final transfiguration of the material universe, foreshadowing the sort of ‘space’ in which the New Jerusalem will descend from heaven. There will be “no temple in the city, for the Lord God and the Lamb are its temple” (Apoc. 21,22). There, he will fully contain creation; but here, it is creation that contains him, imperfectly but truly, in its temples and liturgies.

In this propadeutic universe of ours, he ordained to place his mysterious, glorified presence in that form of matter which is destined to enter into the precarious temples of our human bodies: food and drink. There, within us, that which is contained (Christ) grows to paradoxically contain its very recipient (us), and like the great reversal of center and periphery prefigured in Dante’s cosmos – where the earthly core of perdition and purification suddenly gives way to the converse center of the divine essence in Paradise, and the world is turned inside out and right side up – so it is with Communion.

Grace is just glory under seal, and its propagation on earth through prayer and sacrament is candidly revolutionary. Wherever grace is quietly planted, one day tumultuous glory will shine forth. If the larger portion of the world’s Christians attribute such overwhelming importance to the Eucharist, it is because they see it as one very strategic way heaven is preparing its final sedition against the earthbound plans of this world. Holy time-bombs are being planted in human hearts and church tabernacles, all over our troubled planet. And there’s a wonderful bonus that cheers my heart. The saints tell us that one day, looking back from glory, the enigmas of our crazy human story will finally make sense. “In that day you will ask nothing of me.” (John 16,23)